In the first part, I want to express how delighted I am to be reading this book. I love this book and it’s a very welcome change of pace from the often soul-crushingly depressing things we’ve dealt with in this course. I think it’s a breathtakingly beautiful book that manages to do the dance of dealing with the terrible parts of humanity without becoming a part of that terribleness itself.

But more to the point I want to look at the way that the children in the book, Scout Jem and Dill, go about policing each other and forming their bonds. The three of them interact in all sorts of interesting ways. Jem seems to be the leader, and Scout and Dill sort of do this interesting back and forth where at first Scout seems to be the superior but is later kind of slowly supplanted for complex reasons.

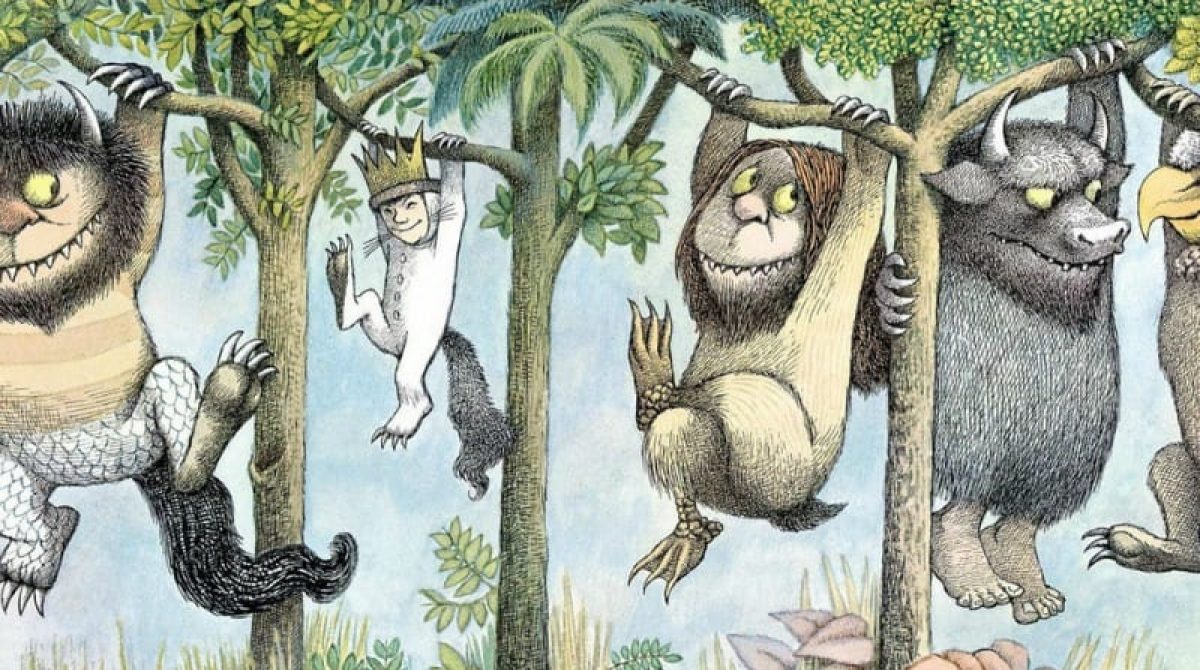

Jem falls into the leader position perhaps initially because he is the eldest of the three, but simple age doesn’t seem like much of it. He is the one who comes up with their “plays” and their games and leads them on their merry adventures of prodding the Radley house, rolling in tires, playing Tarzan, and what have you.

Scout for a long while maintains her status over Dill largely by right of seniority, and also perhaps by force. She’s a quarrelsome little girl and it’s well known that she can beat up Dill and probably does so on several occasions, however in spite of this, she winds up falling behind Dill. I think the main reason for this is that Dill comes up with games. It’s his idea to make Boo Radley come out and he begins instigating their plans and their schemes.

Scout is a rather passive character in fact. She is kind of swept up in and carried along by the plans of Jem and Dill, wrapped up in their actions, and at the mercy of Atticus’s decrees. She is very reactive, not often pro-active, and while her position as a girl seems to contribute to her distancing from Jem and Dill in some small way, I think her reactiveness has her falling behind both of them in their small little hierarchy far before that becomes an issue.

This issue is reflected often in the book. The law, the power, the status in the book, generally side with those who are the active participant, rather than the reactive ones. Tom Robinson is reactive against a situation instigated by someone else, Atticus similarly reacts against the situation and loses. Atticus is a very strong character, but often a reactive one, reacting to the town, to his sister, to Scout’s situation at school, and things generally seem to not work out in his favor.

Atticus and Scout are generally reactive characters, and they tend to lose out in their own separate worlds. How exactly this relates to justice, and who the law sides with, I’m not sure, but it seemed an interesting observation.